Painting the Impossible: What Happens When a Prison Becomes a Neuroarts Lab

For more than three years I lived in a world that had no color. Not metaphorically—literally. In the Los Angeles County jail system, there are no cell windows, no views, nothing that lets the outside world seep in. Light arrives sickly and sour, filtered through fluorescent tubes that hum gleefully as they're chewing on your nerves. Sleep comes in fragments. Noise never does. The place is designed for disorientation: constant noise, constant threat, a schedule that has no compassion anywhere in it.

Once a week, if the guards remembered or felt like it, we went to the roof for an hour or two. Sunlight, yes—but the view of the city was blocked by green mesh panels, a geometry of enforced blindness. Downtown Los Angeles was all around us, close enough to feel its heat rising off the streets, yet intentional design made the entire city vanish. The rest of the week was twenty-four hours a day in a beige box that corroded your mind the way rust claims steel—first a stain, then a weakness, then a collapse.

Then came reception—another tiny shared cell, a dirt patch surrounded by razor wire for “yard time.” After that, High Desert State Prison. Same dirt patch, identical building, identical logic.

And it's not just the physical environment that's deliberately impoverished, it's everything we can touch, hold or care about. Even the things we are allowed to buy all feel like they were bought on the boardwalk—cheap, earnest lies about what real things are supposed to be. For years I couldn't get a real pen, only thin plastic refills, as if handwriting were a skill we no longer needed. I white knuckled hundreds of pages before I realized I could build a pen casing with paper and soap. And the food follows the same logic: punishment disguised as empty calories, a steady diet of things meant to dull rather than sustain. We now know, the brain responds to what it’s given, and here it’s given almost nothing.

But one day, in the chow hall, a small miracle arrived disguised as breakfast. The usual six-ounce plastic bag of nameless “juice”—the color of copper runoff, or of whatever passes for juice when fruit is nowhere in the recipe—was gone. In its place sat a tiny cardboard carton. Real packaging. A printed emblem. And on its front, a cluster of red cherries.

Not rust red. Not the dull oxidized splatter of blood or ochre brick stain you see on old concrete. A bright, clean, living red—the first real red I had seen in years. The color of the accent wall in my home. The color of something that belonged to a world where I once had a life.

We weren’t supposed to take anything from the chow hall, but I put that carton in my pocket like it was contraband worth dying for. Back in my cell, I folded it into a small, perfect box to store my single serving coffee packets. A little cube of forbidden color. I built a shelf for it using paper, soap, and a length of salvaged string—a tiny engineering project so I wouldn’t have to store my single-serve coffee and synthetic sugar packets on the floor. The box sat there like an altar piece: cherries on a white field, bright as a wound and just as honest.

Every morning I looked at that box before I looked at anything else. And for a few seconds, I remembered that the world held color. That somewhere far away, things could be vivid again.

That’s where this story begins—with the hunger for color. With the knowledge of what happens to a mind when everything around it is built to flatten the senses. And with the question that followed me all the way to San Quentin:

What if a single bright red memory could grow into a mural that gives all of us a story worth telling the people we love?

San Quentin isn’t like other prisons; there was just enough openness here for a new kind of work to take root. It's tough, but it isn’t lifeless. The noise, the concrete, the routine—all of that is real. But so is the fog, the light off the Bay, and the sense that the place hasn’t given up on the idea of change. That small opening was enough. It made me think the environment could be shaped, not just endured.

Then I met my Cofounder Kyle and that narrow sense of possibility was enough for us to act. Change wasn’t here yet, but it was close—you could feel institutions paying attention, researchers asking questions, professionals wanting to contribute. But we knew it wouldn't be successful unless the people living and working inside the prison shaped the direction. With support from the administration and partnerships with outside experts, we co-founded San Quentin SkunkWorks as an inside-led innovation lab: a place where we could prototype change and iterate in real conditions. We'd start with research, build solutions that work then scale them.

We chose the name SkunkWorks because it’s a term used in business and engineering fields to describe a focused team built to work beyond the limits of the larger system. It’s also the first thing you build when you want to go to the moon or change the world. Our first task was no less daunting: to reimagine, redesign, and rebuild the physical and emotional landscape of San Quentin from the inside out. Among the projects that grew from that mandate is Chiaroscuro: Light Within the Shadows, which began with a simple question: if the environment shapes us, what happens when we shape it back?

We turned to murals because they let you change the sensory environment at scale—color, symbol, and story all working at once to shift how a place feels and how people experience themselves inside it. Neuroarts tells us that when you alter a space’s emotional and visual cues, stress patterns change and relationships recalibrate. Our plan was simple: gather the truth of this place, translate it into a visual language that could hold its complexity, and embed it directly into the architecture. Only then could we begin to study what environmental change might make possible here. In neuroarts terms, we were planning to create a live study of environmental enrichment—altering color, scale, and symbolism to see how stress, perception, and relationships might shift.

As a research-driven organization, we started with neuroaesthetics, color theory, and a close study of each artist’s visual language so the work would be grounded, intentional, and human. From there we looked for artists who could carry the emotional and cultural weight of this place without simplifying it. We chose FaithXLVII, eL Seed, and Zio Ziegler for different but complementary reasons. Faith paints the human condition with a clarity and emotional honesty systems like this rarely allow. eL Seed listens first, then builds sweeping calligraphic structures that turn community stories into something elevated and connective. Ziegler works in a visual vocabulary of archetype, density, and psychological depth—work that speaks not just to what’s seen, but to the interior life a place like this tries to erase. To prepare them, we gathered hundreds of stories from residents, staff, teachers, doctors—anyone whose life had passed through these corridors. And when the mural work began, it wasn’t outsiders decorating a prison—it was a ragtag group of incarcerated people, artists and professionals leading from within. We raised the money, wrote the grants, secured partnerships with a global art-production firm and national paint suppliers, and then we were on the scaffolds—brushes in hand, paint in our hair, grinning like lunatics. The first murals with FaithXLVII and her son, Keya Tama, were completed in June, drawing statewide attention.

Faith XLVII’s mural, ‘The Heart of the World,’ at the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center on July 11, 2025. Photo Credit: Marcus Casillas San Quentin News.

Faith XLVII’s mural, ‘The Heart of the World,’ at the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center on July 11, 2025. Photo Credit: Marcus Casillas San Quentin News. A mural painted by Keya Tama at the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center on July 11, 2025. Photo Credit: Marcus Casillas San Quentin News.

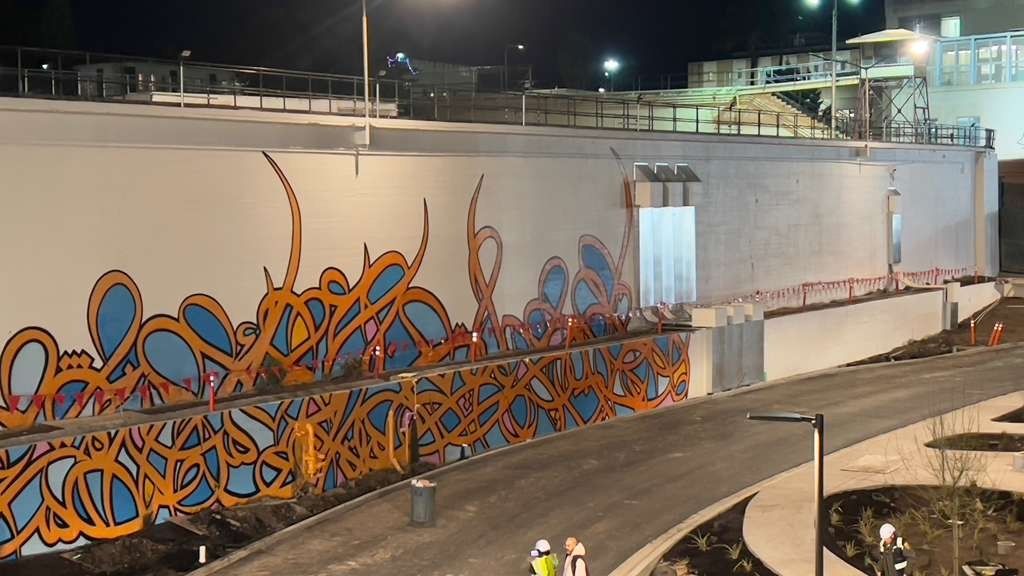

A mural painted by Keya Tama at the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center on July 11, 2025. Photo Credit: Marcus Casillas San Quentin News.Now we’ve painted the walls around Governor Newsom’s $300 million education complex, with eL Seed creating a 325-foot mural paired with a matching piece on the Orpheum Theatre in San Francisco. The inside mural and its Orpheum counterpart form a single visual circuit between the prison and the city—one story told across two walls.

The newly painted mural on the Orpheum Theater Wall. Photo credit: San Quentin SkunkWorks.

The newly painted mural on the Orpheum Theater Wall. Photo credit: San Quentin SkunkWorks. The companion mural inside San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. Photo credit: eL Seed.

The companion mural inside San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. Photo credit: eL Seed.eL Seed works in a language that’s equal parts calligraphy, architecture, and light. His murals aren’t images so much as structures—braided letterforms carrying messages about coexistence and seeing one another differently. That’s why we brought him here. His work asks the viewer to slow down and decode, and in a place built around haste, fear, and misrecognition, that shift matters.

The Orpheum matters because it pulls the work into public view. It’s iconic, impossible to ignore, and woven into the daily life of the city. Thousands of people pass it every day, and soon they’ll be passing our stories too—told through a collaboration between a world class artist and the people who live and work inside San Quentin.

And the work keeps expanding. The Orpheum mural is one part of it; the new education complex is another, and inside the new building, Zio Ziegler is creating a major interior piece that will anchor a rotating gallery designed to hold work from world-class artists and incarcerated creators together for the first time—a cultural infrastructure this place has never had. We’re calling it Exhibit A.

Our work is just beginning. To carry it forward, we need professionals at the top of their fields—lighting designers, acousticians, architects, neuroscientists, color theorists, material and textile specialists, environmental psychologists, and artists who understand how the built environment shapes the brain. We need people who can help us redesign everything a place communicates: its light, its sound, its textures, its cues, its emotional climate. If you’re ready to join us—to study this, strengthen it, and help build the future of neuroarts where it matters most—reach out.

We will call you back from a recorded line.