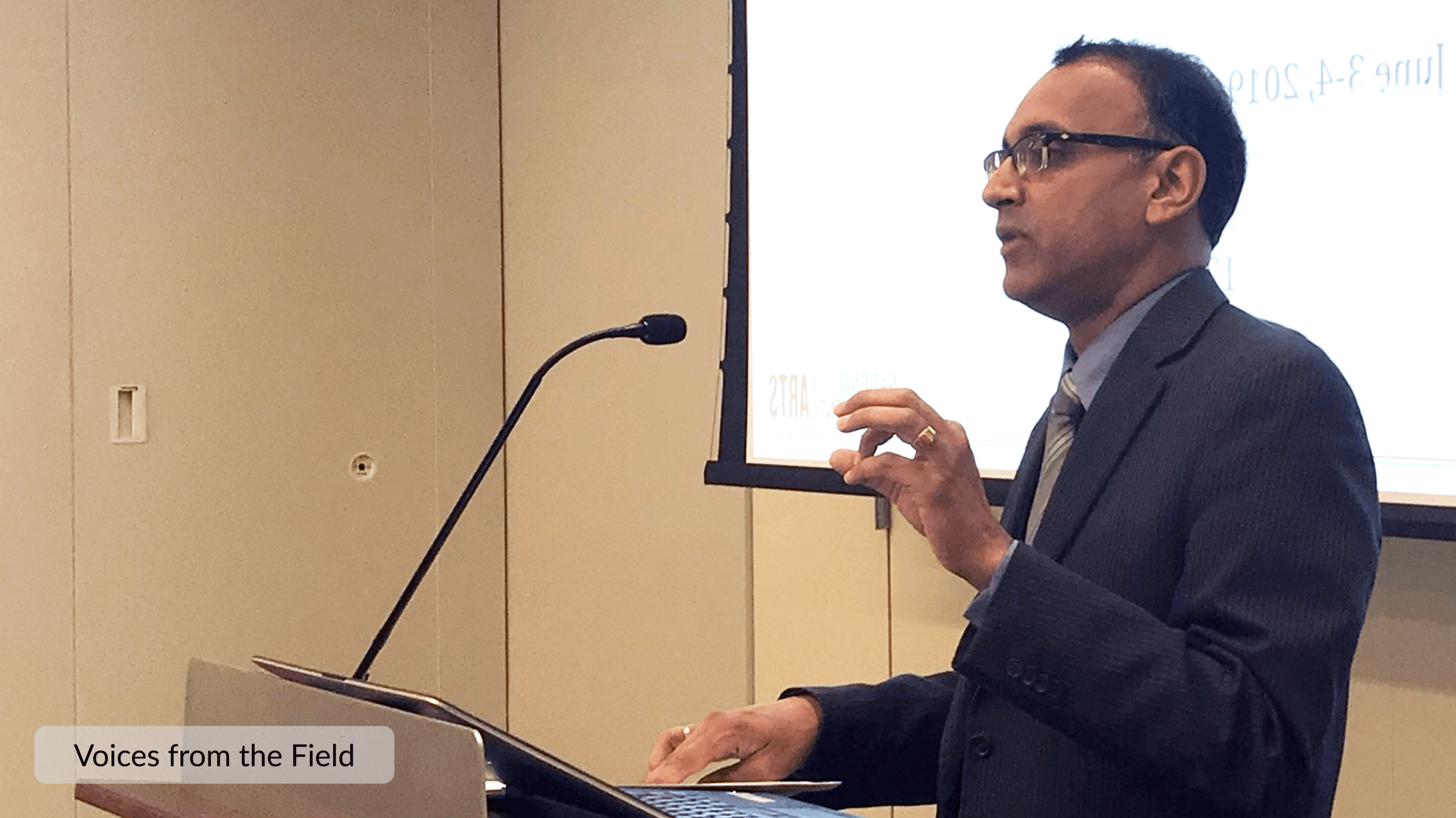

Voices from the Field: Sunil Iyengar

What first inspired you to explore the connection between the arts, health, and/or science?

In my role overseeing research at the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), I gravitated quickly to the measurable benefits of arts participation—and learning in the arts—across the lifespan. I also recognized a public need for better understanding the arts’ therapeutic possibilities in addressing certain health conditions.

In my own case, this perspective came from 10 years as a journalist covering health policy, biomedical research, and the medical device industry. Although the arts never surfaced in this context, I realized that closer attention from scientists and healthcare professionals would bring more rigor and relevance to the job of articulating the arts’ societal benefits.

To be clear: I am not saying that artists or the arts must carry, as their primary burden, the responsibility of improving health or combating diseases. But if we want to try and express the arts’ value to everyday life, then we have a duty to glean what insights we can, not just from the humanities but also from the fields of neuroscience, psychology, medicine, and, yes, economics.

In your view, what makes the arts and aesthetic experiences uniquely powerful tools for advancing health and wellbeing—and how does your work contribute to translating that potential into practice?

C.S. Lewis on reading great literature: “I become a thousand men and yet remain myself…. I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.” In creating or witnessing art, we are taken beyond ourselves, even while our senses and feelings are awakened and intensified.

What does this mean for health? For starters, there is the science of human flourishing, which researchers in the field of positive psychology have pioneered. There is also the neuroscience of creativity and learning through the arts. And there are large longitudinal datasets, and small experiments, permitting researchers to track health-related outcomes from arts participation among children and adults.

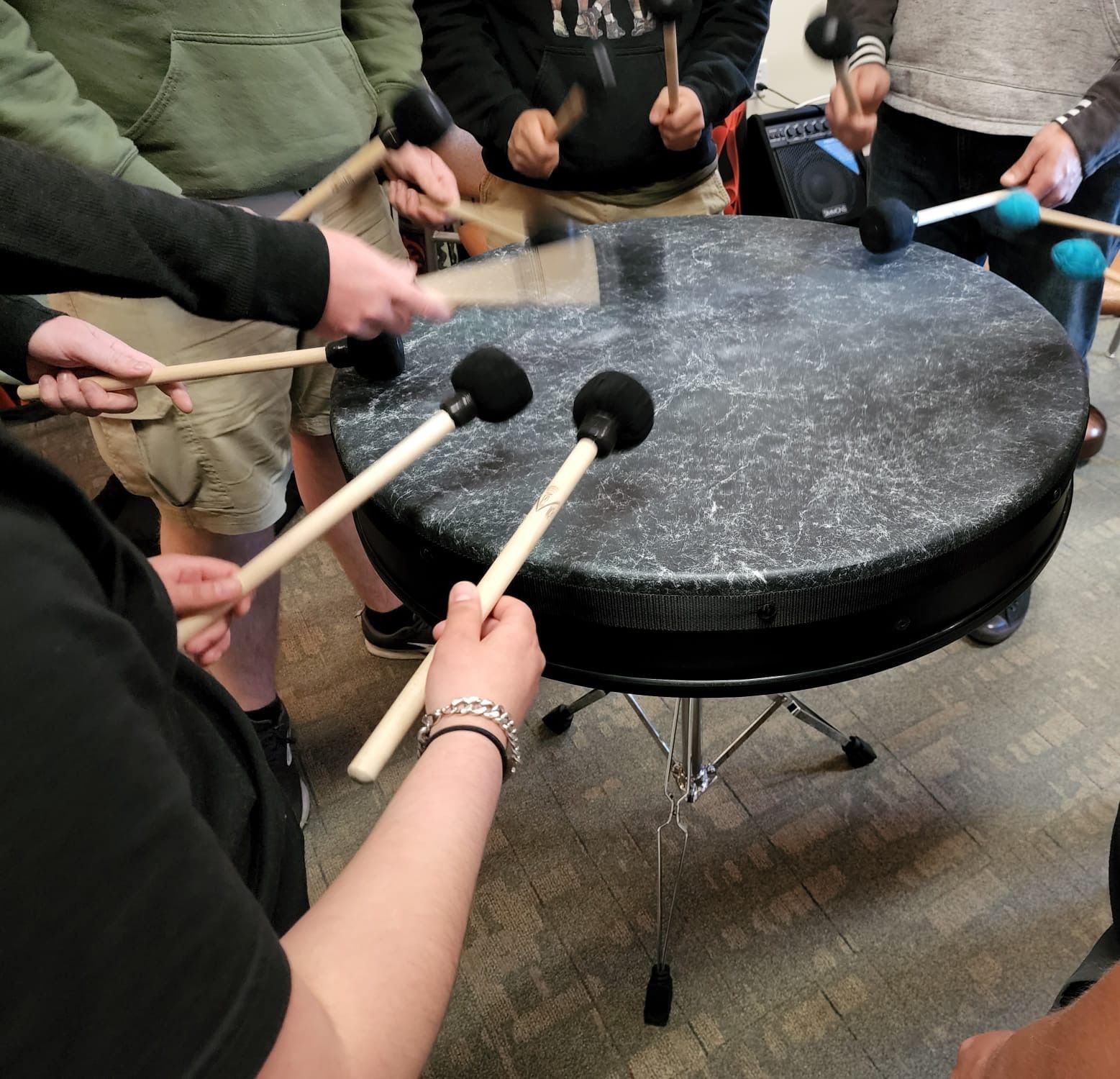

But, in our time, some of the most promising research about the arts and health has centered on music therapy and other music-based health interventions. Both the National Institutes of Health and the NEA have activated such studies through federal funding. More broadly, the study of creative arts therapies (including music therapy, art therapy, and dance/movement therapy) has proved highly rewarding.

Service Members participate in music therapy classes at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska. Photo courtesy of the NEA.

Service Members participate in music therapy classes at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska. Photo courtesy of the NEA.Clinical researchers, as part of the Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network with the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, have discovered that creative arts therapies can reduce PTSD symptoms and enable recovery from traumatic experiences. In military-connected populations, such therapies also can foster the ability to experience hope and gratification, and they can reduce isolation and stigma associated with traumatic brain injuries and related psychological illnesses.

Finally, through the NEA’s Research Grants in the Arts (RGA) and Research Labs programs, we fund interdisciplinary studies about the arts’ relationship to health and well-being across the lifespan. In recent years, we have supported studies of music and dance/movement in older adults with neurodegenerative disorders; of art therapy in pediatric cancer patients; and the arts in reducing stress and burnout in healthcare workers. We also have published research reports—for example, on arts-based strategies for combating the opioid crisis.

Veterans at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida, participate in a group therapy session with board-certified dance/movement therapist Brittni Cleland. Photo by Devin Pickering

Veterans at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida, participate in a group therapy session with board-certified dance/movement therapist Brittni Cleland. Photo by Devin PickeringWhat challenges do you see in building a more cohesive and equitable neuroarts ecosystem?

Language can be a barrier. I mean the vocabulary that different specialties use, not to mention the challenges they face in reaching the public directly. We need more clarity on terms used in science and policy circles, but we also need a readily understood vernacular for talking about the different components of the arts and health, and for making any shared goals visible to people from different backgrounds.

Looking ahead, what is one bold idea or hope that you have for the future of neuroarts?

Even as we race to work across disciplinary siloes, let’s not lose track of the arts themselves! We need to understand at a more profound level the “active ingredients” of arts and cultural experiences, and acknowledge that the arts revel in ambiguity, even a sense of magic and mystery. Let’s do justice to this complexity by learning to appreciate and listen to great art and artistic processes.

Artwork depicting masks created by veterans during art therapy sessions at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Photo by Andres Hernandez

Artwork depicting masks created by veterans during art therapy sessions at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Photo by Andres Hernandez